Friday Find: Adam Hocker (1828-1907) Family Bible

I was recently contacted by a reader who is in possession of Adam Hocker’s family bible. I’m hoping to put him in touch with a living descendant.

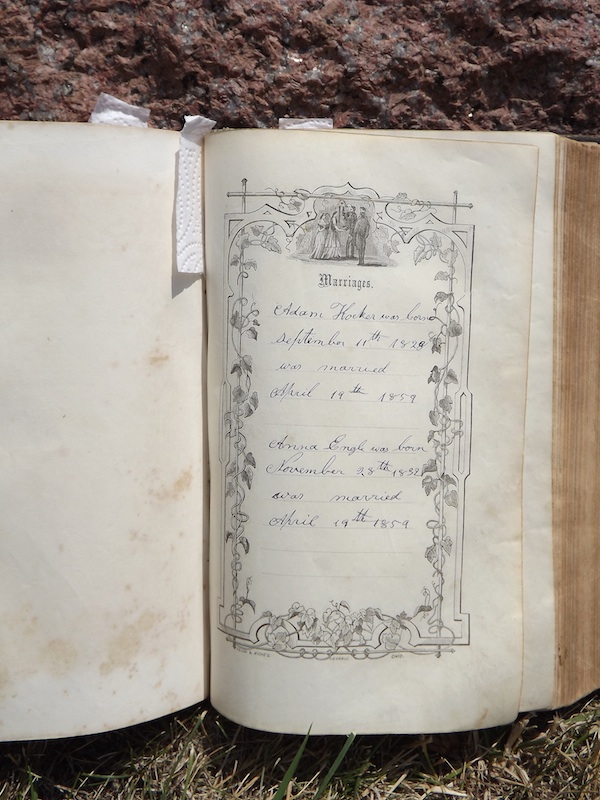

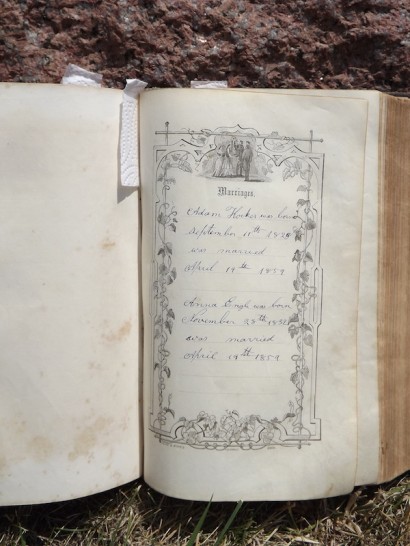

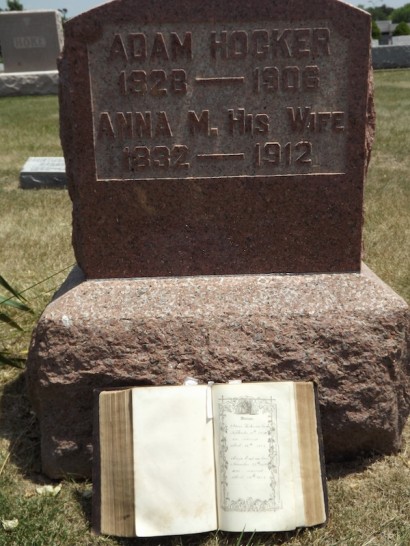

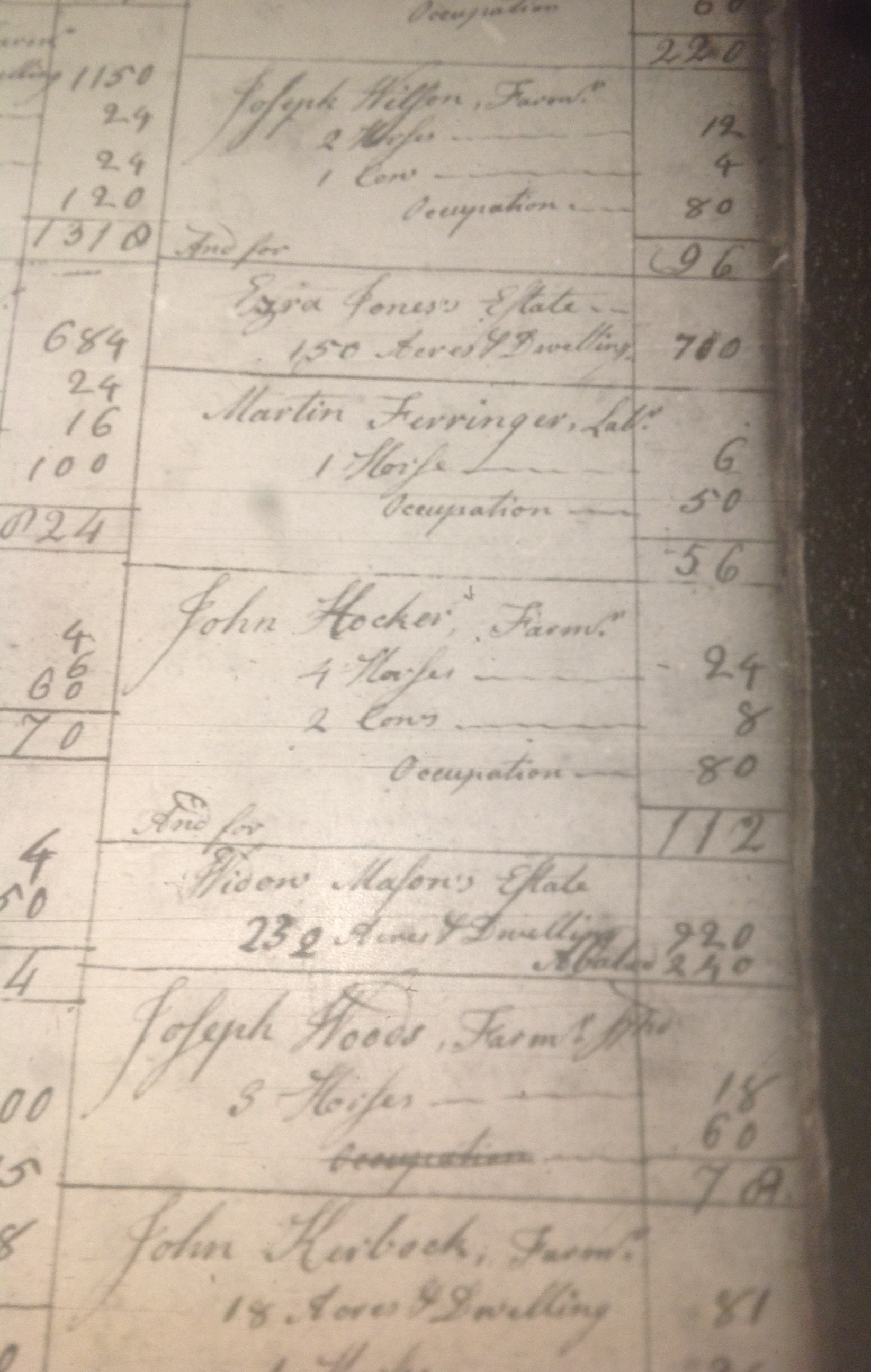

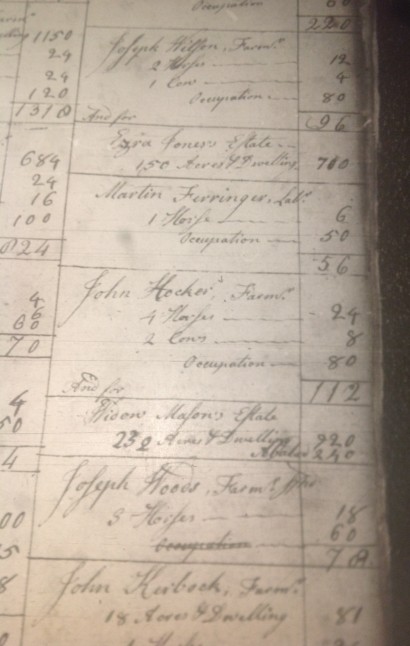

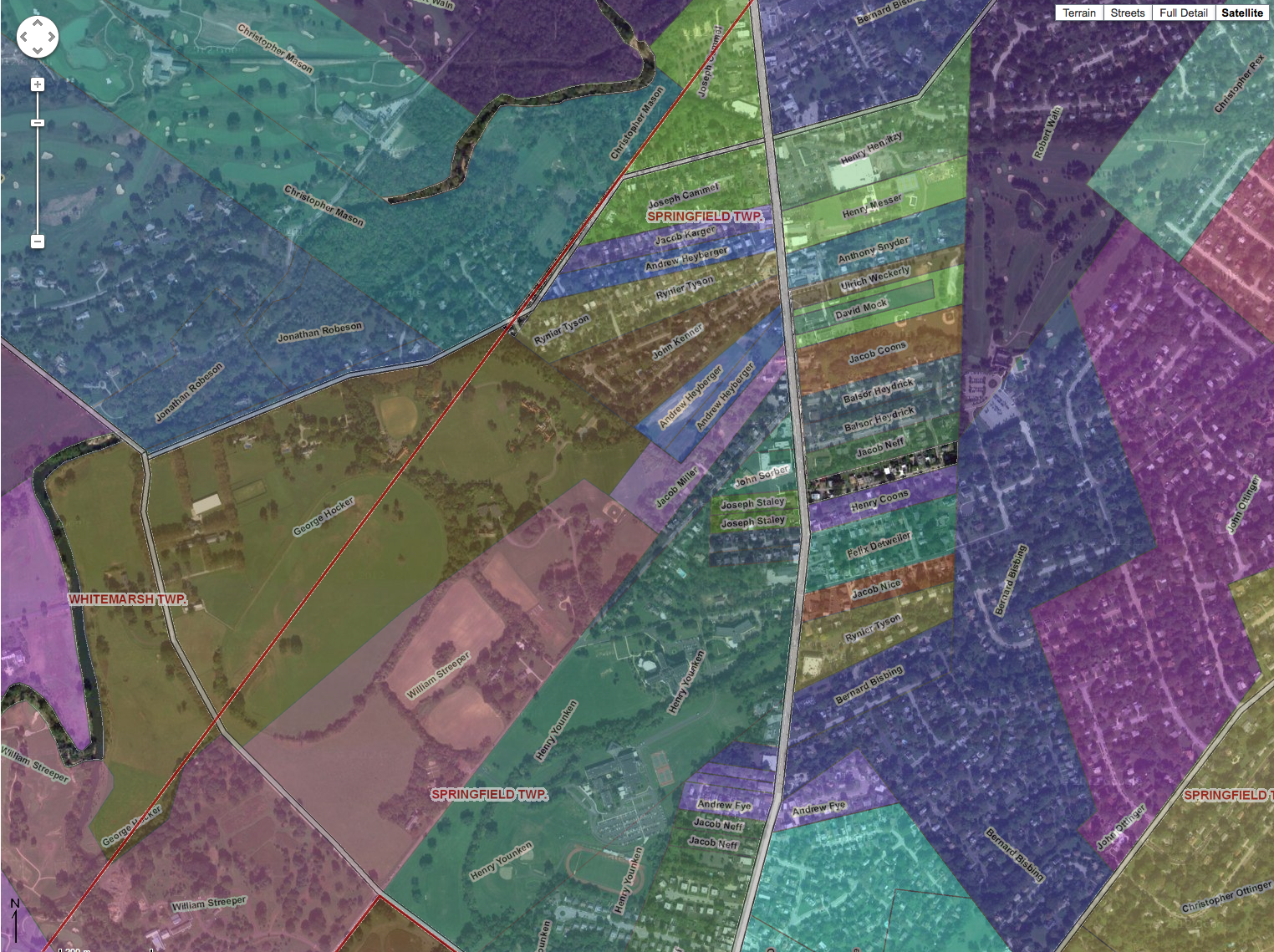

Adam Hocker was born 11 Sep 1828 in Derry Township, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania to Reverend John Hocker and his wife Catharine Sterling.1 He married Anna M. Engle, daughter of Jacob and Nancy (Moyer) Engle, on 19 Apr 1859 in Montgomery County, Ohio.2 Anna was born 21 Nov 1832 in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.3

Adam was a farmer in Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio and deacon in the River Brethren Church. He died on 8 Sep 1907 and was buried in Fairview Cemetery, Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio.4 Anna died 5 years later on 25 May 1912 of tuberculosis and was buried with her husband on 27 May 1912.5

Adam and Anna (Engle) Hocker had five children:

- Benjamin E. Hocker was born 23 Jan 1860 in Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio and died 24 Jan 1933, Phoenix, Maricopa County, Arizona.6 Benjamin married Mary Kinsel about 1887 in Ohio. The couple had at least four children:

- Jesse Albert Hocker was born 21 Oct 1884 in Ohio and died Aug 1972 in Durango, La Plata County, Colorado.7 He married Martha Jane Gribble on 24 Oct 1916. She was born 21 Oct 1892 and died Feb 1980 in Durango, La Plata County, Colorado. The couple had at least two children.

- Anna R. Hocker was born 5 Apr 18868 in Ohio and died Aug 1970 in Durango, La Plata County, Colorado.9

- Unknown Hocker was born sometime between 1886 and 1891 in Ohio and likely died before 1900 in Ohio.10

- Susan Goldie Hocker was born 2 Feb 1891 in Ohio and died Apr 1987 in Durango, La Plata County, Colorado. She married Emory Edward Smiley about 1918.

- Elizabeth E. Hocker was born 19 Nov 1861 and died 19 May 1879 in Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio of consumption (tuberculosis).11

- Ellen Hocker was born about 1864, likely in Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio and died sometime after the 1930 census enumeration. She married Franklin Etter about 1888. I believe Franklin and Ellen (Hocker) Etter had children:

- Maude E. Etter

- Elmer F. Etter

- Anna Mae Etter

- Charles Etter

- Clara Etter

- Anna M. Hocker was born 28 Jun 1865 and died 30 Jan 1918 in Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio.12 She married Deacon Levi Seth Hoke on 18 Sep 1884. He was born 25 Dec 1862 or 1863 and died 24 Feb 1933.13 He was a farmer and member of the River Brethren Church. They are buried in Fairview Cemetery in Englewood, Ohio. I believe Levi and Anna (Hocker) Hoke had children:

- Ambrose Hoke

- Albert Hoke

- Mary Edna Hoke

- Letitia Hoke

- Mary Alice Hoke

- Catharine (Kathryn) Hocker was born 6 Mar 1867 and died 25 Nov 1952 in Randolph Township, Montgomery County, Ohio.14 She married John David Betz on 26 Dec 1886 in Montgomery County, Ohio. He was born 12 Jul 1861 and died 15 Oct 1924.15 They are buried in Fairview Cemetery in Englewood, Ohio. I believe John and Katie (Hocker) Betz had children:

- Herman (or Homer) Betz

- Audry Betz

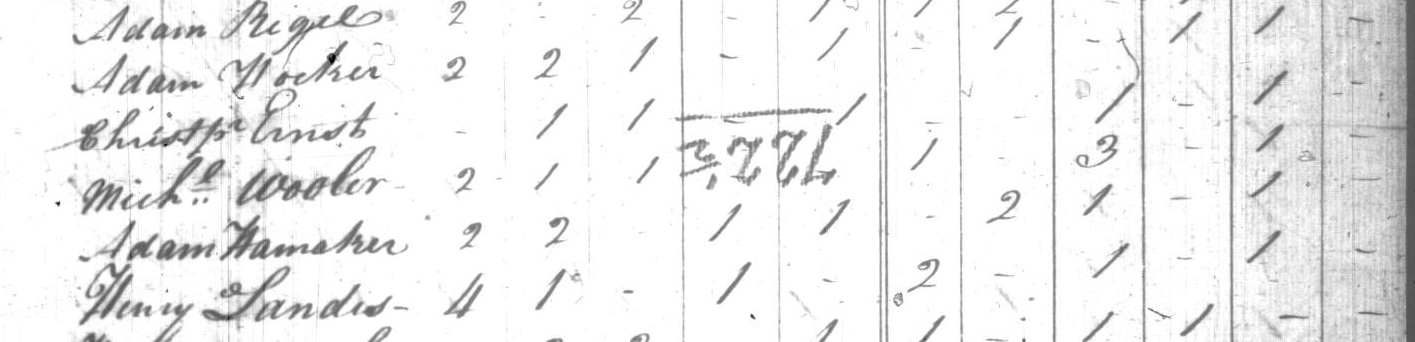

Adam Hocker is my first cousin 5 times removed. My 4G grandfather was the younger brother of Adam’s father John Hocker.

Images © Harold Rothery