AncestryDNA Rolls Out New Features

Over the last couple of weeks new features have been appearing in my AncestryDNA account. A couple can be considered “keeping up with the Jones'” additions, but some are unique. Let’s take a look at them.

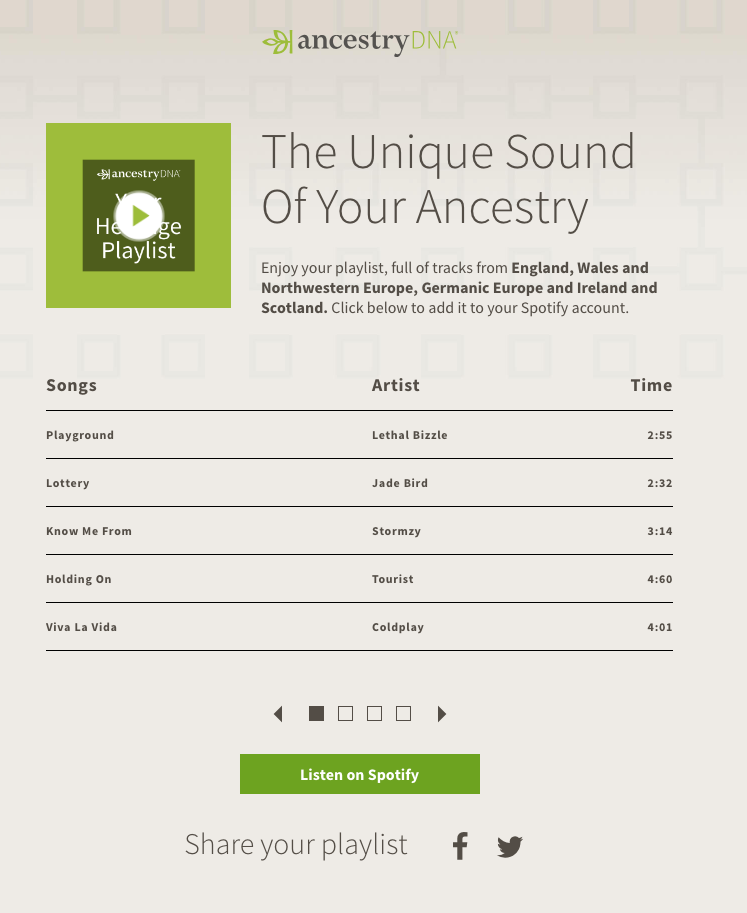

The Sound of You

The first to appear was the “What’s the sound of you?” banner, highlighting a partnership between AncestryDNA and Spotify. The tool allows you to create a playlist based on the regions associated with your DNA. You select the regions and the tool creates a playlist with artists from those locations. You can add the playlist to your Spotify account and share it on social media.

It’s a creative and playful way to highlight music from your ancestral regions. I haven’t seen anything like it on any of the competitors’ sites. But it doesn’t teach me anything about my family history or heritage. Nor does it help me connect with my genetic cousins or solve my genealogical brick walls. Nice, but there are tools I would have liked to see much more.

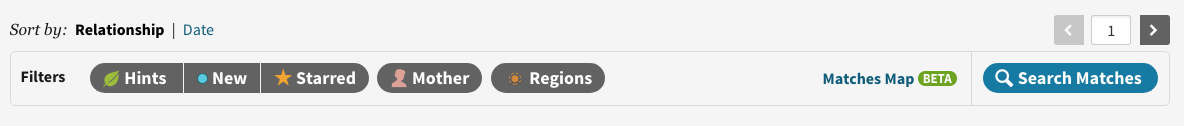

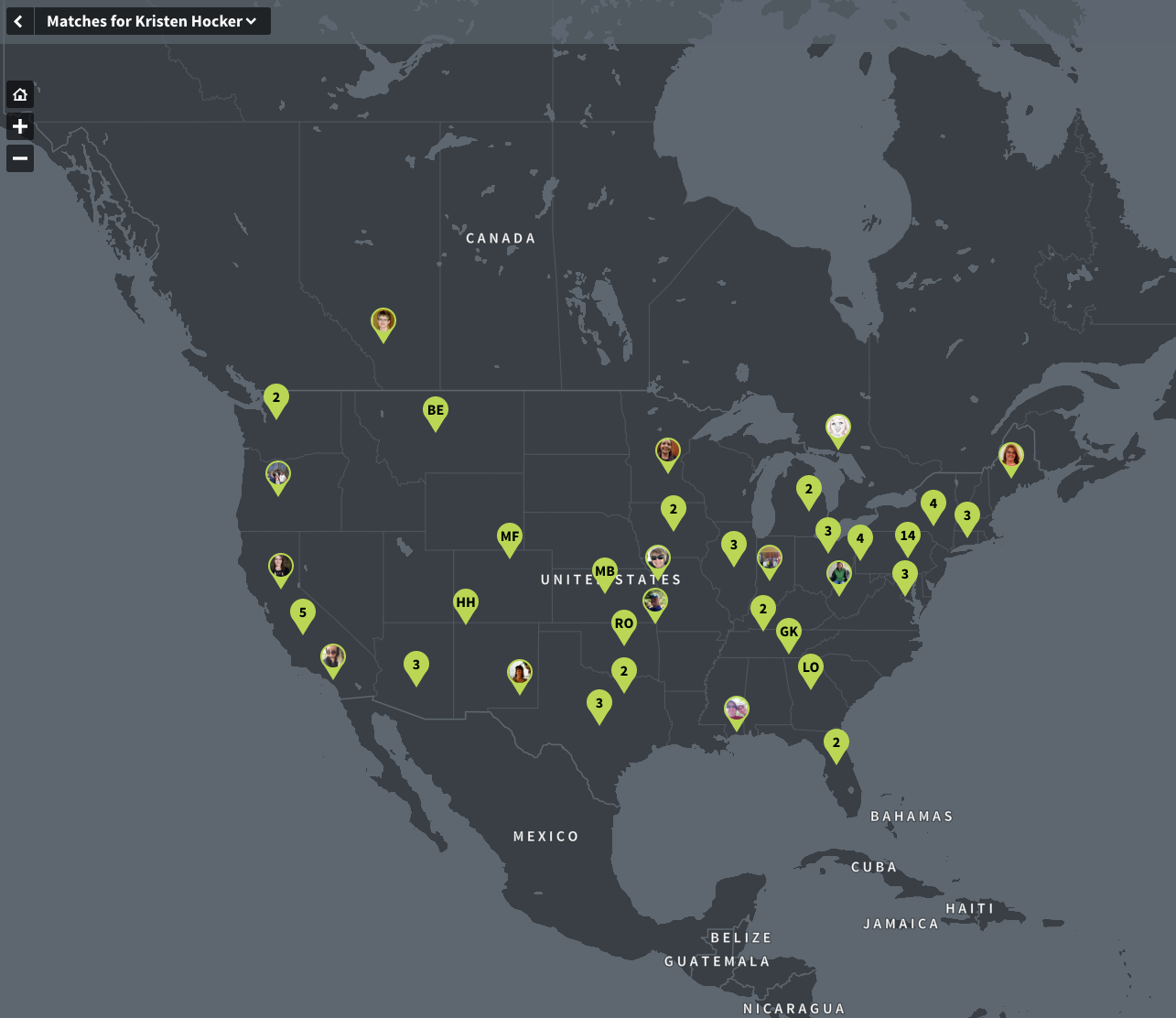

Matches Map

The Matches Map is still in beta. When you click the “Matches Map” link in the header, it will show the locations of your AncestryDNA matches on a map. This is separate from and different to the Map and Locations you can find on each match’s page.

Knowing your match’s physical location is helpful when you need to identify their possible ancestors. It helps you identify just which John D. Ancestorson is the correct one in your search.

However, it requires that your match has entered a location in their Ancestry profile. In my experience, not many do. Furthermore, while the map make a nice visual, it’s no more useful than simply displaying the match’s location with their username—which Ancestry had already been doing.

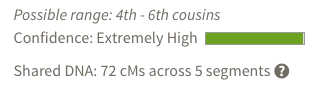

Shared DNA

I wrote about using the MED Better DNA extension for Chrome to display my notes for an individual match on the main match list. My notes included the amount of shared DNA and any information I’d come up with regarding how I connected with that DNA match.

Apparently, Ancestry has been paying attention to how people are using their site, because they added the Shared DNA amount to the information they display with each match on the list. Yay!

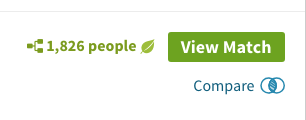

Compare Ethnicities

Clicking the “Compare” button allows you to compare ethnicities with a match. There are buttons on both the DNA Matches page and the individual DNA Match page for an individual.

I’ve seen this elsewhere, but Ancestry’s visual display is on a separate screen and includes not only the shared ethnicity percentages and map, but also a list of shared matches (below Ethnicity Estimates, not included in screenshot). Furthermore, clicking “view all” in the shared matches, bring you to a list of all the matches you share with that person.

For me, ethnicity is interesting, but, given our current knowledge and ability to tie DNA to ethnicities, not particularly helpful in solving my genealogical mysteries.1 A match and I share a Northwestern Europe ethnicity? Great! Can that tell me which European ancestor we descend from? Can it tell me which village they came from? Or even, can it tell me which country they came from? Not so much.

AncestryDNA Traits

The most recent addition to the toolset is AncestryDNA Traits.2 It allows you to examine what your DNA can tell you about 18 traits, including: taste (sweet, savory, bitter, cilantro aversion), hair curl and thickness, eye color, male hair loss, chin dimple, skin pigmentation, finger length, freckling, ear lobe type, etc.

Ancestry will identify where those traits come from around the world (“Where does your curly hair come from?”) and permit you compare your traits against your DNA matches (“Does your cousin also have the DNA for blue eyes?).

And you can get all this information without further testing—for $19.99 per kit.

Conclusions

Ancestry sure has been busy. They’re rolling out a lot of new… stuff. But to be honest, I’m not sure what value most of it has to me—the user, the customer.

I use Ancestry—and now AncestryDNA—for one thing: to build my family tree. At first, I accomplished this by searching Ancestry’s databases and accessing primary records. I built my tree based on the conclusions I drew from that research. It was great because I had the convenience of accessing the information from my home.

When AncestryDNA came along I used my genetic matches and their knowledge of their family trees (or ones that I built) to add to my tree or to identify specific families to research so that I can break down brick walls. It’s great because DNA gives me another form of evidence that can be used, even where I lack information from the genealogical record (ie. paper trail).

Do these additions help me to match my genealogical tree to my genetic tree? Do they help me see patterns or make connections? Do they help me prove relationships? Do they help me build my family tree?

If I measuring these new tools and products against my goals for using the site, most of these additions are fun or interesting diversions. I might try them out, but I likely won’t be using them with any regularity. They do not assist me in reaching my goals and therefore, ultimately, do not add value. My 2¢.

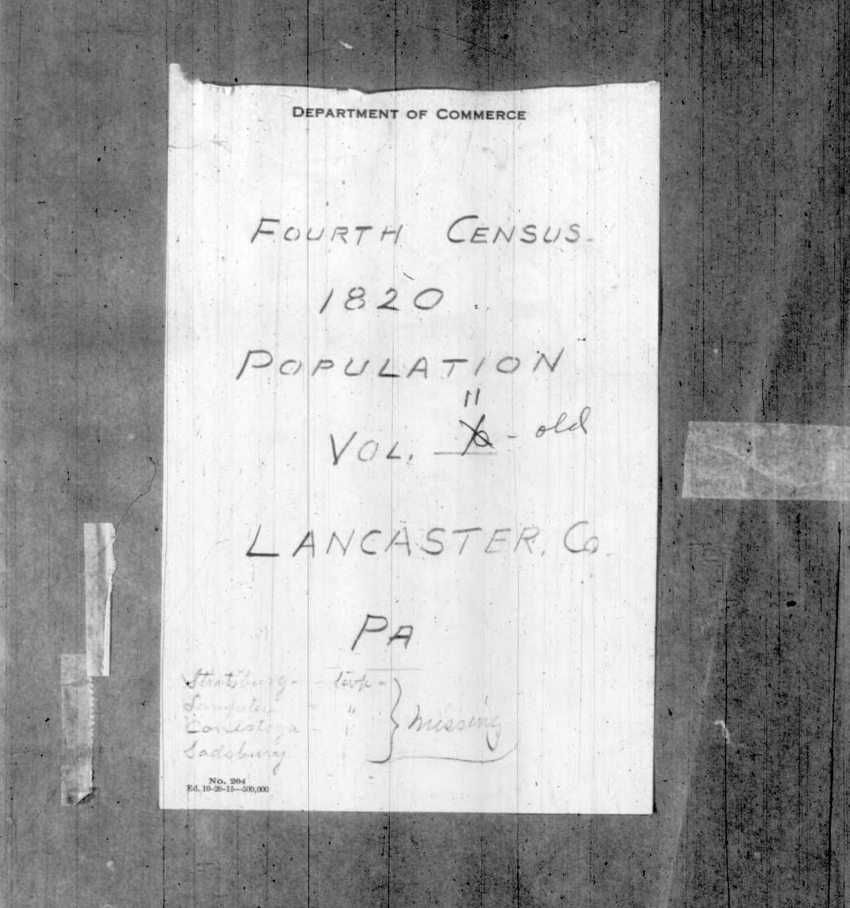

The United States Federal Census is one of the most widely used resources for genealogists. Online access to the census indices and images is available through a variety of subscription services like

The United States Federal Census is one of the most widely used resources for genealogists. Online access to the census indices and images is available through a variety of subscription services like